January 28th, 2026

—

How everyday experiences determine whether quality is used or avoided

When I first audited an industrial equipment business many years ago, the owner made it clear that having a certified quality management system was not something he wanted. Certification was a requirement from his customers rather than a strategic choice, and while he agreed to implement it, there was a clear sense of reluctance behind the decision. Quality, in his mind, meant extra work, unnecessary paperwork, and disruption to how the business already operated.

That perspective was formed when earlier in his career, he had worked as an employee in an organisation that was also certified, and the experience had left a lasting impression. The system in that organisation existed on paper, but it arrived without involvement or ownership from the people expected to use it. Processes were introduced without consultation, and internal audits felt more like inspections than conversations. Nonconformances were raised in a way that discouraged openness, and engaging with quality often resulted in blame rather than improvement. He described the environment as rigid and unforgiving, and over time he learned that the safest way to operate was to comply when necessary and disengage whenever possible.

Years later, as a business owner, that experience followed him into his own organisation. When the quality management system was introduced, it met the requirements, but it sat at arm’s length from daily work. The system existed, but it didn’t shape decisions or behaviours in any meaningful way, and while the business remained certified, quality wasn’t something people naturally referred to.

Over time, that began to change. As the system became more embedded, the owner started to notice patterns that challenged his earlier assumptions. Errors were identified earlier, handovers became clearer, and conversations about problems happened before issues escalated.

More importantly, he became aware of something else. He didn’t want his people to associate quality with the same frustration and resistance he had once felt. So, he deliberately changed how quality showed up in the business. Staff were involved earlier in discussions, audits became constructive rather than confrontational, and processes were shaped around real work rather than theory. Quality stopped being something imposed on people and started becoming something they participated in.

Today, that same owner is one of the strongest advocates for quality in any of the organisations I work with. Not because certification is required, but because he has seen firsthand how culture determines whether a system gains traction or remains a formality. The system itself didn’t change first; the experience of working with it did, and once that shifted, everything else followed.

Organisations with a strong, aligned culture don’t just have quality systems on paper; they live with them and use them. As Forbes explains in Company Culture Matters More Than Ever in 2025, “research shows that employees who feel connected to their organisation’s culture are four times more likely to be engaged at work and nearly six times more likely to recommend their workplace to others,” underlining the link between cultural engagement and how people actually show up in their jobs.

—

Let’s look at this another way – a quality management system is a lot like a gym membership.

You can be required to sign up, pay the fees, and even show your card when asked, but that doesn’t mean you want to be there. If your only experience of the gym is being corrected constantly, watched closely, or made to feel like you’re doing everything wrong, you learn quickly that turning up comes with discomfort, and over time you stop engaging unless you absolutely have to.

That doesn’t mean exercise is the problem. It means the environment has taught you that participation carries a cost.

Now imagine owning the gym.

You still care about results, safety, and standards, and you still expect people to train properly, but you change how the space works. You make it welcoming rather than intimidating, you explain why techniques matter, and you support progress instead of punishing mistakes. People are encouraged to show up, even when they’re not perfect, because improvement is treated as part of the process rather than a failure.

The equipment hasn’t changed, and neither have the rules, but participation looks very different.

Quality systems behave in much the same way. People don’t avoid the system because they dislike quality or standards; they avoid it because past or present experiences have taught them that engaging with it leads to criticism, extra work, or exposure. When the culture shifts and it becomes safer to participate, the system no longer needs to be enforced, because people start using it naturally as part of their work.

Where Culture Changes the Experience of Quality

What determines whether a quality management system gains traction or stalls is not the structure of the system itself, but how it is experienced day to day by the people expected to use it. The shift that matters most is often subtle, but it shows up clearly in behaviour, conversations, and how safe it feels to engage with quality at work.

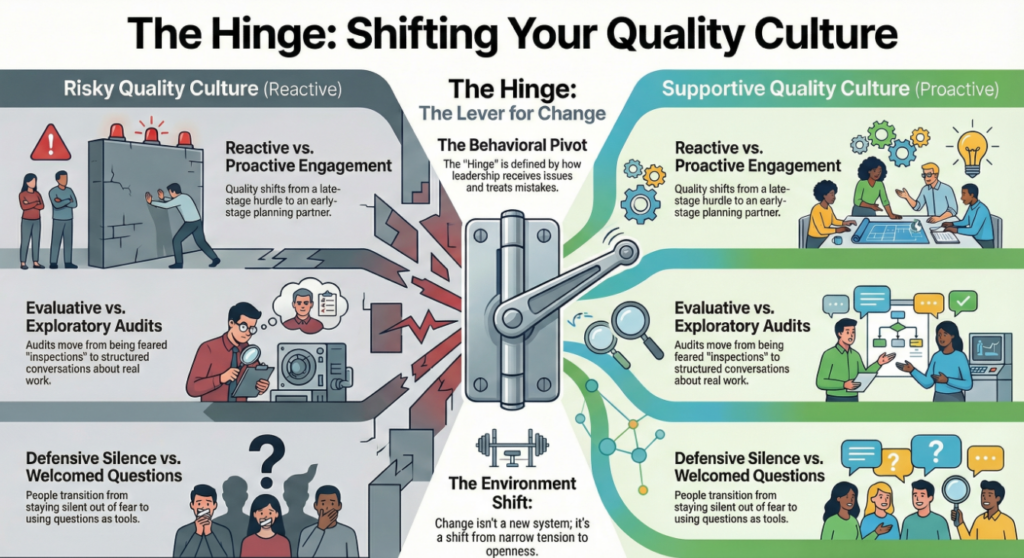

The first change shows up in reactive versus proactive engagement. In environments where quality feels risky, engagement is reactive, with issues raised late and quality brought in once decisions are already made. As the environment shifts, quality starts to appear earlier in conversations, not because people are instructed to involve it, but because it feels useful and safe to do so. This is where the behavioural pivot becomes visible, as people move from protecting themselves to participating more openly.

That shift carries directly into evaluative versus exploratory audits. When the culture is tense, audits feel evaluative, with a focus on what went wrong and who missed something. As the environment becomes more supportive, audits turn into exploratory conversations about how work happens, what trade-offs exist, and where the system can better support the organisation. The audit process itself hasn’t changed, but the experience of participating in it has.

The third change is often the most subtle, but also the most revealing, and it shows up in defensive silence versus welcomed questions. In risk-laden cultures, people stay silent, choosing caution over curiosity because asking questions has historically come with consequences. As the environment shifts, questions are welcomed and treated as tools for understanding rather than signs of failure, which makes it easier for issues to surface early and improvement to continue beyond the audit cycle.Across all three areas, the pattern is consistent. The system remains intact, but the environment shift changes how people experience quality, and that change in experience drives behaviour. It is this shift, rather than new controls or tighter procedures, that ultimately gives a quality management system traction.

Next Steps for You

- Pay attention to when quality is involved early and when it only appears at the end.

- Notice how questions and issues are received, not just whether they are raised.

- Observe whether audits feel like evaluations or genuine conversations about work.

- Look for where people protect themselves instead of participating openly.

- Make one deliberate change that makes engaging with quality feel safer.

—

View comments

+ Leave a comment