January 14th, 2026

—

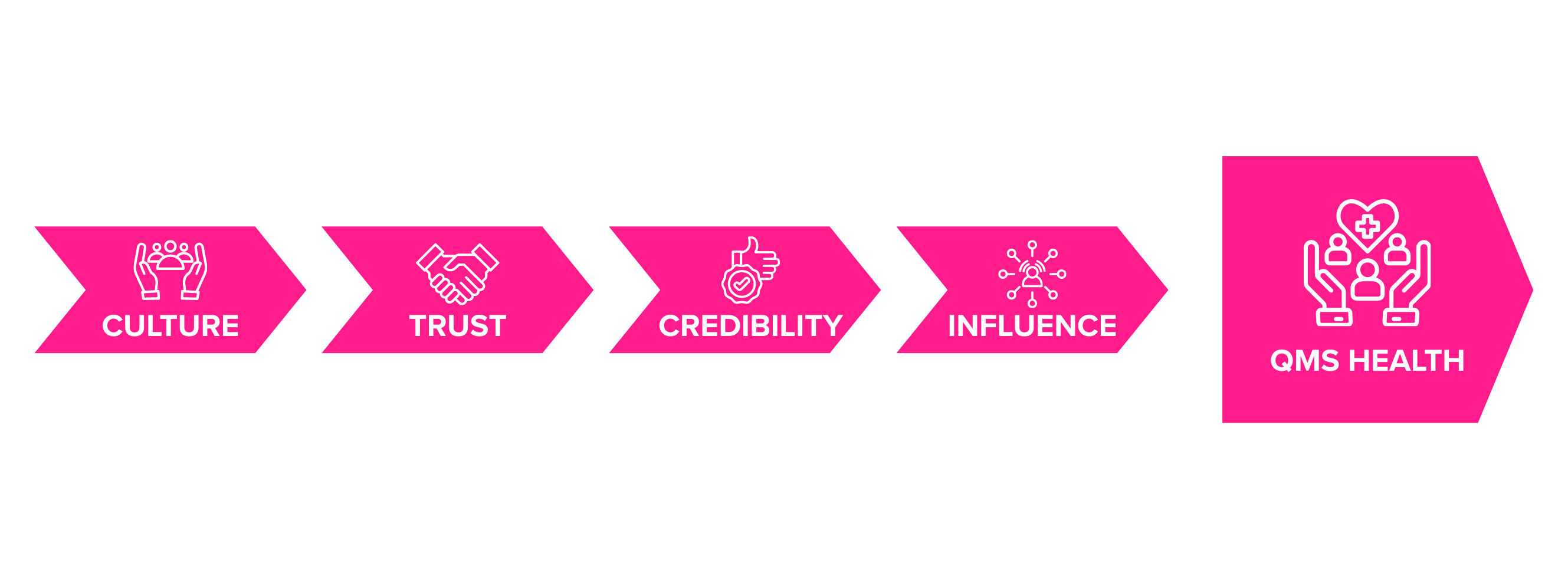

The cultural conditions that determine whether quality has influence

I worked with an organisation where quality had a clear owner. There was a dedicated quality role, years of experience, and a strong grasp of the standard. The system itself was well documented. Procedures were current. Audit results looked respectable. On paper, it all stacked up.

What stood out wasn’t what I saw in the documents. It was what I noticed in meetings.

Quality rarely came up unless something had already gone wrong. Operational decisions were made, timelines were locked in, and then quality would be looped in at the end, usually with a request to “just check it.” When issues did surface, the conversation shifted quickly into explanation mode. People justified why something happened instead of exploring what could be improved.

When I spoke privately with a few team members, a pattern emerged. They weren’t careless. They weren’t disengaged. They were cautious.

They told me they’d raised issues in the past, only to feel blamed or interrogated. Not overtly. Nothing dramatic. Just enough questioning, enough defensiveness, enough subtle signals that it wasn’t worth the effort. Over time, they learned to manage problems within their own teams rather than bring them into the open.

Quality wasn’t avoided because it lacked competence.

It was avoided because it felt risky.

As a result, the quality management system continued to exist, but mostly on the edges of the work. It was something people referred to after decisions were made, rather than something that shaped them.

Issues didn’t disappear. They were contained until they couldn’t be. When they finally surfaced, they did so under pressure, with limited options and little appetite for reflection. By then, the focus was on justification rather than learning.

What was striking was that none of this came down to a lack of knowledge or effort. The system was sound. The people were capable. The problem sat in the space between them.

The culture around quality had trained people how to behave. Not through policy or instruction, but through experience. It taught them when to speak up, when to stay quiet, and what happened if they didn’t get that judgement right.

And over time, credibility never formed. The system existed, but it wasn’t trusted enough to influence decisions early.

A published study, Understanding the nexus between organizational culture and trust: The mediating roles of communication, leadership, and employee relationships found that organisational culture plays a key role in shaping communication patterns, employee relationships, and trust within organisations. While leadership behaviours influence outcomes, culture is central to trust, and that trust is what gives quality leaders credibility in practice.

—

—

A quality management system is a bit like traffic rules in a busy city.

When people trust the system, they move with confidence. They stop at red lights because they expect cross-traffic to do the same. They merge smoothly because indicators are used predictably. The rules fade into the background and traffic flows.

When that trust isn’t there, behaviour changes.

Drivers hesitate at green lights, scanning the intersection because they’re not convinced others will stop. They avoid certain routes altogether because past experience tells them it’s not worth the risk. Some edge through amber lights rather than stopping, worried they’ll be rear-ended if they hesitate. Others sit back and wait, even when they technically have right of way.

The rules haven’t changed. The signals still work. But confidence in how the system will play out has eroded, so people adapt their behaviour to protect themselves.

Quality works the same way.

When people don’t trust how quality issues will be handled, they pause before raising them. They manage problems locally instead of putting them into the system. They wait until something is unavoidable before speaking up. Not because they don’t care, but because experience has taught them to be careful.

The system still exists. But its influence weakens because credibility in how it operates has been lost.

How Credibility Takes Place in Practice

What this story highlights is that a quality management system doesn’t succeed or fail on documentation alone. Its health is shaped by a set of underlying conditions that influence how quality is experienced, discussed, and acted on across the organisation.

Those conditions build on one another, and together they determine whether quality has real influence or remains on the edges of the work.

Culture

Culture is the starting point because it shapes what feels normal. It reflects the behaviours people see rewarded, tolerated, or avoided. Over time, culture teaches people when it’s safe to speak up, when to stay quiet, and how seriously quality is taken in practice.

If the culture discourages openness or prioritises speed over learning, quality conversations will naturally sit on the edges of the work, regardless of how strong the system is on paper.

Trust

Trust develops from repeated experience within that culture. It’s built when people believe that raising issues will be handled fairly and consistently, without blame or unnecessary consequences.

When trust is low, people become selective about what they share and when. They manage problems locally, delay escalation, and protect themselves first. That behaviour isn’t a lack of commitment to quality. It’s a rational response to the environment.

Credibility

Credibility sits at the point where trust becomes personal. It reflects whether the people associated with quality, regardless of title, are seen as worth engaging early.

Credibility isn’t created through authority or technical expertise alone. It forms when people trust how quality conversations will unfold. Without that trust, credibility never really establishes, and quality remains reactive.

Influence

Influence is what credibility enables. When credibility exists, quality is invited into discussions before decisions are locked in. Issues surface earlier. Trade-offs are discussed openly rather than justified later.

Where credibility is missing, quality may still exist as a function, but it lacks influence. It is consulted late, if at all, and has limited ability to shape outcomes.

QMS Health

QMS health is the visible result of all the conditions that come before it. A healthy system is not one with perfect documentation, but one that people use, trust, and engage with early enough to make a difference.

When culture, trust, credibility, and influence are weak or misaligned, the system may still operate, but it will struggle to deliver consistent outcomes. When those inputs are strong, QMS health follows as a natural consequence.

Next Steps for You

- Observe how quality conversations actually happen across the organisation

- Notice when quality is invited into decisions and when it is avoided

- Pay attention to how issues are received, not just how they are recorded

- Look for behaviours that make it easier or harder for people to speak up

- Focus on reinforcing trust-building behaviours before changing documents

—

Great article – thanks Jackie

Thank you so much Susan. I’m happy that you enjoyed it. All the best.

Jackie